|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

MISRATAH - At night, from the courtyard of the prison, you can hear the sound of the sea. The sound of the waves of the Mediterranean, a hundred meters from the fence of the detention centre. We are in Misratah, 210 km east of Tripoli, in Libya. The prisoners are all Eritrean asylum seekers arrested off Lampedusa or in the suburbs of Tripoli. Victims of the collateral effects of the Italo-Libyan agreement against immigration. They are more than 600 people, between 20 and 30 years old, including 58 women and several children and babies. The majority was arrested two years ago, but none of them has been to a trial in court. They sleep on the ground in rooms with no windows, 4 meters per 5, up to 20 people in each one. At least they are allowed to stay in the courtyard, under the watchful eyes of the police. Their fault? Having tried to reach Europe in order to seek asylum.

MISRATAH - At night, from the courtyard of the prison, you can hear the sound of the sea. The sound of the waves of the Mediterranean, a hundred meters from the fence of the detention centre. We are in Misratah, 210 km east of Tripoli, in Libya. The prisoners are all Eritrean asylum seekers arrested off Lampedusa or in the suburbs of Tripoli. Victims of the collateral effects of the Italo-Libyan agreement against immigration. They are more than 600 people, between 20 and 30 years old, including 58 women and several children and babies. The majority was arrested two years ago, but none of them has been to a trial in court. They sleep on the ground in rooms with no windows, 4 meters per 5, up to 20 people in each one. At least they are allowed to stay in the courtyard, under the watchful eyes of the police. Their fault? Having tried to reach Europe in order to seek asylum.The Eritrean diaspora passes through Lampedusa and Malta. Since 2005 at least 6,000 refugees from the former Italian colony have landed on Sicilian shores, fleeing Isaias Afewerki’s dictatorship. The situation in Asmara continues to be critical. Amnesty International denounces arrests and harassments of opponents and journalists. And the tension with Ethiopia remains high, so that at least 320,000 Eritreans are forced to the military service for an indefinite period, in a country of 4.7 millions inhabitants. Every year many desert the army and run away to rebuild their lives. Most of them stop in Sudan: more than 130,000 people. The others instead, cross the Sahara, reach Libya and take a boat to Europe.

The first time I heard about Misratah it was in the spring of 2007, during a meeting in Rome with the director of the High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Tripoli, Mohamed al Wash. Few months later, in July 2007, thanks to an Eritrean association, we managed to get in contact by phone with a group of Eritrean prisoners. They complained for the overcrowded conditions, the lack of hygiene, and their precarious state of health, particularly for pregnant women and babies. They also accused some police officers for having committed sexual harassment. At that time Amnesty International had already expressed its deep concern about the deportation of Eritreans arrested in Libya. And on 18th September 2007, the Eritrean diaspora organized demonstrations in a few major European capitals to sustain them.

The first time I heard about Misratah it was in the spring of 2007, during a meeting in Rome with the director of the High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Tripoli, Mohamed al Wash. Few months later, in July 2007, thanks to an Eritrean association, we managed to get in contact by phone with a group of Eritrean prisoners. They complained for the overcrowded conditions, the lack of hygiene, and their precarious state of health, particularly for pregnant women and babies. They also accused some police officers for having committed sexual harassment. At that time Amnesty International had already expressed its deep concern about the deportation of Eritreans arrested in Libya. And on 18th September 2007, the Eritrean diaspora organized demonstrations in a few major European capitals to sustain them. The director of the camp, Colonel ‘Ali Abu ‘Ud, knows well the international reports on Misratah, but denies them: "Everything they told you is false" he says proudly. He seats at his desk, dressing jacket and tie, behind a bouquet of fake flowers in his office on the first floor. From the window I see a crowded courtyard with more than 200 detainees. Abu 'Ud visited in July 2008 some reception centres in Italy, with a Libyan delegation. He talks about Misratah as a five-star hotel compared to the other Libyan detention camps. And probably he is right... After insisting for quite some time, a colleague of the German radio, Roman Herzog, manages to get the permission to speak to the Eritrean refugees. We go into the courtyard, and we separate. I interview F., 28 years old, who has spent 24 months in this prison. While he speaks I realize that I'm not listening to him. Actually I’m simply imagining to be in his shoes. We have roughly the same age, but he is wasting the best years of his life, forgotten in this prison.

The director of the camp, Colonel ‘Ali Abu ‘Ud, knows well the international reports on Misratah, but denies them: "Everything they told you is false" he says proudly. He seats at his desk, dressing jacket and tie, behind a bouquet of fake flowers in his office on the first floor. From the window I see a crowded courtyard with more than 200 detainees. Abu 'Ud visited in July 2008 some reception centres in Italy, with a Libyan delegation. He talks about Misratah as a five-star hotel compared to the other Libyan detention camps. And probably he is right... After insisting for quite some time, a colleague of the German radio, Roman Herzog, manages to get the permission to speak to the Eritrean refugees. We go into the courtyard, and we separate. I interview F., 28 years old, who has spent 24 months in this prison. While he speaks I realize that I'm not listening to him. Actually I’m simply imagining to be in his shoes. We have roughly the same age, but he is wasting the best years of his life, forgotten in this prison. In the opposite corner of the courtyard, Roman has been able to speak for a while to a refugee far from the security officers, who follow our work and translate everything to the chief. His name is S. He speaks freely: "Brother, we are in a bad situation here, we are tortured, mentally and physically. We have been here for two years and we don’t know what is reserved for us in the future. You can see it by yourself, look!”. Meanwhile, the interpreter joins them and informs the Colonel, who interrupts the interview and asks S. if he does not want to return to Eritrea. Roman invites the refugee to walk fast towards the rooms before the director stops them again. “We are all Eritreans – he keeps on saying -. I came to Libya in 2005. We seek political asylum, because of the situation in our country. But the world doesn’t care about us. It's not easy to stay two years in prison, without any comfort. We're in jail, we are not allowed to see the world outside. All we need is freedom".

In the opposite corner of the courtyard, Roman has been able to speak for a while to a refugee far from the security officers, who follow our work and translate everything to the chief. His name is S. He speaks freely: "Brother, we are in a bad situation here, we are tortured, mentally and physically. We have been here for two years and we don’t know what is reserved for us in the future. You can see it by yourself, look!”. Meanwhile, the interpreter joins them and informs the Colonel, who interrupts the interview and asks S. if he does not want to return to Eritrea. Roman invites the refugee to walk fast towards the rooms before the director stops them again. “We are all Eritreans – he keeps on saying -. I came to Libya in 2005. We seek political asylum, because of the situation in our country. But the world doesn’t care about us. It's not easy to stay two years in prison, without any comfort. We're in jail, we are not allowed to see the world outside. All we need is freedom".Inside the room, 18 people sit on blankets and dirty mattresses on the floor. The room measures 4 meters by 5. There are no windows. "It is too overcrowded - says S. – We can’t see the sunlight and there is no air supply. In the summer it’s very hot, and people get sick. The same in the winter, it's very cold at night”. It’s the end of November, and the prisoners are wearing sandals and light pullovers. The next room is larger, but there are many more people, all women and children. But it’s too late to speak with them. The security officers have reached Roman and interrupt his work. They want him to speak with a refugee they have chosen. “I am also a prisoner” he tells my colleague, who refuses to listen to him and starts talking with another refugee. J., he is 34 years old and he says he has been in 13 different prisons in Libya: “Some of us have been here for four years. Personally, I spent three years in this camp. We are in the worst situation. We haven’t committed crimes, we are just demanding political asylum. At least tell us why! Nobody is informing us. What's going to happen to us? Even the UNHCR doesn’t tell us anything. I've lost hope... I was 60 kg when I entered, now my weight is 48, imagine why .. "

Colonel Abu 'Ud follows the conversation with the help of the interpreter, he can’t stand it any more: “Do you want to return to Eritrea?” he asks J. interrupting the interview. “I'd rather die – he replies – as every one here”. The director becomes angry, and starts threatening him: “If you want to go to Eritrea we will repatriate you in a single day". "They forbid us to speak with you," says J. to Roman. The director is furious. He screams "Tell them that they will all be returned". Then he comes close to Roman and orders: "Finished". Roman tries to protest, "We’ve finished" ‘Abu ‘Ud repeats, while two agents pull us towards the exit. Before leaving the courtyard, the Colonel speaks loudly to all the refugees: “If you feel mistreated here, we’ll organize your return immediately. You have already refused to return to your country, that’s why you are here. But each one of you is free to return to Eritrea! Who wants to go to Eritrea?”. “None!”, answers the crowd. “Did you see?! – the director cries again to Roman - Now we’ve really finished. "

Colonel Abu 'Ud follows the conversation with the help of the interpreter, he can’t stand it any more: “Do you want to return to Eritrea?” he asks J. interrupting the interview. “I'd rather die – he replies – as every one here”. The director becomes angry, and starts threatening him: “If you want to go to Eritrea we will repatriate you in a single day". "They forbid us to speak with you," says J. to Roman. The director is furious. He screams "Tell them that they will all be returned". Then he comes close to Roman and orders: "Finished". Roman tries to protest, "We’ve finished" ‘Abu ‘Ud repeats, while two agents pull us towards the exit. Before leaving the courtyard, the Colonel speaks loudly to all the refugees: “If you feel mistreated here, we’ll organize your return immediately. You have already refused to return to your country, that’s why you are here. But each one of you is free to return to Eritrea! Who wants to go to Eritrea?”. “None!”, answers the crowd. “Did you see?! – the director cries again to Roman - Now we’ve really finished. " We go back to the colonel’s office. With a very nervous voice, he tries to convince us of his commitment. The Eritrean embassy sent officials to identify the prisoners twice. But the refugees refused to meet them. They even organized a hunger strike. Understandably, I think, since they would be persecuted in their homeland. And Libya should know it, since on 27th August 2004, a deportation flight to Eritrea was hijacked in Sudan by its own passengers. But the concept of political asylum is not clear to the Libyan authorities. In their mind, they are just patrolling the European border. And if they catch Eritreans or Nigerians, there’s no difference. If Eritrean refugees refuse to go back to their country, their detention will be without limit of time. Unless they get the chance to be resettled in Europe by the UNHCR, or they manage to escape.

We go back to the colonel’s office. With a very nervous voice, he tries to convince us of his commitment. The Eritrean embassy sent officials to identify the prisoners twice. But the refugees refused to meet them. They even organized a hunger strike. Understandably, I think, since they would be persecuted in their homeland. And Libya should know it, since on 27th August 2004, a deportation flight to Eritrea was hijacked in Sudan by its own passengers. But the concept of political asylum is not clear to the Libyan authorities. In their mind, they are just patrolling the European border. And if they catch Eritreans or Nigerians, there’s no difference. If Eritrean refugees refuse to go back to their country, their detention will be without limit of time. Unless they get the chance to be resettled in Europe by the UNHCR, or they manage to escape. Haron is 36 years old. He left a wife and two children in Eritrea when he escaped in 2005, after 12 years of unpaid military service. He has spent two years in the prison of Misratah. Sweden has just accepted his request for resettlement. He will leave three days after our visit, on 27th November 2008, with a group of 26 Eritrean refugees from Misratah, including many women. The resettlement is the only card which the UNHCR can play in Libya. The first 34 Eritrean women left Misratah in November 2007 and were resettled in Italy. For Rome it was the first resettlement of refugees since the crisis in Chile in 1973. But the operation was censured by the press office of the Italian Ministry of Interior, in order to avoid any eventual controversy with the right wing xenophobic parties.

Haron is 36 years old. He left a wife and two children in Eritrea when he escaped in 2005, after 12 years of unpaid military service. He has spent two years in the prison of Misratah. Sweden has just accepted his request for resettlement. He will leave three days after our visit, on 27th November 2008, with a group of 26 Eritrean refugees from Misratah, including many women. The resettlement is the only card which the UNHCR can play in Libya. The first 34 Eritrean women left Misratah in November 2007 and were resettled in Italy. For Rome it was the first resettlement of refugees since the crisis in Chile in 1973. But the operation was censured by the press office of the Italian Ministry of Interior, in order to avoid any eventual controversy with the right wing xenophobic parties.Since then, about 200 refugees were transferred from Misratah, to Italy (70), Romania (39), Sweden (27), Canada (17), Norway (9) and Switzerland (5). The person who gives me these figures is Osama Sadiq. He’s the project coordinator of the International Organization for Peace Care and Relief (IOPCR). An important Libyan NGO, which pretends to be non-governmental even if it contains some former officials of the ministry of interior and security. IOPCR is so influential that the UNHCR has access to Misratah only under its coverage. Yes, in a country crossed every year by thousands of Eritreans, Sudaneses, Somalis and Ethiopians refugees, the UNHCR has less power than an NGO. Actually Libya has never signed the UN convention on refugees, but allows the UNHCR to work in his country, even without an official agreement. Fighting for the release of refugees detained in Misratah could break such a weak diplomatic balance. That’s why the UNHCR prefers to work with a low profile, avoiding to criticise Libya.

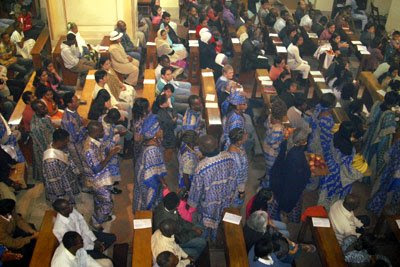

In any case the majority of the prisoners has no chance to be resettled by the UNHCR. For them, the only exit way is to escape from the detention centre. Koubros is one who did it. I meet him on the stairs of the church of San Francesco, near Dhahra, in Tripoli, after the Mass of Friday morning. A group of Eritreans in queue, are waiting the Caritas office to open. He spent one year in Misratah. He was arrested in Tripoli during a raid in the district of Abu Selim. He managed to escape leaving the hospital where he had been taken to after he got sick in prison. Once back in Tripoli, he was arrested again, and taken to the prison of Twaisha, close to the airport. Some friends collected 300 U.S. dollars and corrupted a policeman who let him out. He sits near Tadrous, another Eritrean who has just been released from the prison of Surman. He was caught in the sea, on a boat sailing to Lampedusa, and then sentenced to 5 months of jail. During the detention he got scabbies. We ask him to accompany us to Gurgi, a suburb of Tripoli, where the Eritreans live. He says it is too dangerous. Eritreans live hidden in the city. Our presence may alert the police and cause a raid. Y. doesn’t think so. He lives in a different area. We follow him.

In any case the majority of the prisoners has no chance to be resettled by the UNHCR. For them, the only exit way is to escape from the detention centre. Koubros is one who did it. I meet him on the stairs of the church of San Francesco, near Dhahra, in Tripoli, after the Mass of Friday morning. A group of Eritreans in queue, are waiting the Caritas office to open. He spent one year in Misratah. He was arrested in Tripoli during a raid in the district of Abu Selim. He managed to escape leaving the hospital where he had been taken to after he got sick in prison. Once back in Tripoli, he was arrested again, and taken to the prison of Twaisha, close to the airport. Some friends collected 300 U.S. dollars and corrupted a policeman who let him out. He sits near Tadrous, another Eritrean who has just been released from the prison of Surman. He was caught in the sea, on a boat sailing to Lampedusa, and then sentenced to 5 months of jail. During the detention he got scabbies. We ask him to accompany us to Gurgi, a suburb of Tripoli, where the Eritreans live. He says it is too dangerous. Eritreans live hidden in the city. Our presence may alert the police and cause a raid. Y. doesn’t think so. He lives in a different area. We follow him.The taxi stops on a dirty street near Shar'a Ahad 'Ashara, the eleventh road, in Gurgi. The apartment is owned by a Chadian family, who rents two small rooms on the first floor to seven Eritreans. We take off our shoes before we enter. The floor is covered with rugs and blankets. Five people sleep In this room they sleep. The television, connected to the large satellite dish on the roof, shows music videos of Eritrean singers. It’s a safe place, they say, because the entrance of the house passes through the Chadian family, which lives here since many years. The refugees moved here recently, after the last raids in Shar'a 'Ashara. Now when they hear the police alarm they keep quite. They offer us chocolate, a tomato sauce with bread, 7Up and pear juice.

We continue to talk about their experiences in Libyan prisons. Each one of them has been arrested at least once. And each one managed to escape thanks to corruption. You just need to pay from 200$ to 500$ to a policeman, and they let you go. Money comes with Western Union through the Eritrean diaspora network of solidarity in Europe and America.

Robel also spent one year in Misratah. He shows us the asylum seeker certificate issued by the UNHCR. It is valid till 11th May 2009. But the document doesn’t make him feel safer: "A friend of mine was arrested all the same, police ripped it in front of his eyes." During his detention, he wrote an appeal to the international community, with a group of six Eritreans students.

On the wall, near the poster of Jesus, I see a black and white picture of a few year old child. Next to it somebody wrote her name: Delina. I know her. She was playing this morning on the stairs of the church, with Tadrous. She also will risk her life at sea. "The important thing is to arrive in the international waters," explains Y.. The Eritreans intermediaries (dallala) who organize the crossings, have different reputations. There are unscrupulous ones and others you can be trusted. But the risk remains high. I cannot stop thinking about it, on my return flight to Malta. Comfortably seated and quite bored, I browse the address book where I wrote the email addresses of the Eritreans we met in Tripoli. A month ago, an Ethiopian friend gave me the telephone number of a guy stranded in Tripoli after he failed to cross the sea. Gibril. I tried to call him many times, but his cell phone was always switched off. I keep hearing the echoes of the ununderstandable message in Arabic. I hope he is safe somewhere in Italy or Libya. And not... Good luck, Delina.

(My special thanks to Roman Herzog who contributed to this article and without whom I wouldn’t have done this trip)

Download our report on Libya: Escape from Tripoli