|  |  |  |  |  |  |

I ask him to remember, but it sounds difficult for him. His memory removed everything of those painful and interminable three years. Then, little by little, his mind goes back to the past. Outhman said he saw many refugees being deported. One Congolese originary of RDC, in 2006, who until now is reported to be missing, according to his family. And a Kurdish family, father, mother and five children, deported to Turkey. And a Sri Lankan man, repatriated despite his wife was regularly living in Cyprus. Another chapter alone should be dedicated to the mental health of detainees. Outhman repeats it several times. He saw many men crying as children, and losing hope. He himself repeatedly attempted suicide. After all, it was the only way to escape. The other option was to become crazy. Ali, an Iranian, had no problem when he was arrested. Then he started to change, spending all the day in delirium and washing continuously his hands. He died one month after his repatriation. Another Iranian, Sajjad, became paranoiac. He saw conspiracies against him everywhere. He was irascible. One day the police brought him to the psychiatric hospital Athalassa, in Nicosia. Also Khalid, a young Palestinian, was hospitalized there. He used to run naked in the corridor, always ready to pick a fight for any reason. Another Palestinian boy instead, Mohamed, profited of every opportunity to cut his wrists. He said he wanted to die… they wanted to deport him, but he actually grew up here in Cyprus, where he arrived with his family when he was a child.

Block 10 is a section of the Central Prison in Nicosia. The day after I met Outhman, I decided to go there. I entered easily, telling the police I was a friend of C., one of the detainees Outhman put me in contact with by telephone. The cells are situated on the two sides of a long corridor, closed by a door. In the corridor there is a television, tables and air conditioning. The cells measure two meters by two meters and fifty. With a single bunk bed. Between the two mattresses there is less than one meter of distance. Inside the cells there is neither air conditioning nor heating. The detainees are about fifty. They are free to stay in the narrow closed corridor. But they can go out in the courtyard only once a day, for one hour. Sometime they receive visits from Theophany, a sister of the parish of Saint Joseph, in Larnaca. She brings them clothes and she prays with the Christian ones. Less often they receive visits by UNHCR officials. For the time remaining, there is absolutely nothing to do in Block 10, from morning to evening.

Block 10 is a section of the Central Prison in Nicosia. The day after I met Outhman, I decided to go there. I entered easily, telling the police I was a friend of C., one of the detainees Outhman put me in contact with by telephone. The cells are situated on the two sides of a long corridor, closed by a door. In the corridor there is a television, tables and air conditioning. The cells measure two meters by two meters and fifty. With a single bunk bed. Between the two mattresses there is less than one meter of distance. Inside the cells there is neither air conditioning nor heating. The detainees are about fifty. They are free to stay in the narrow closed corridor. But they can go out in the courtyard only once a day, for one hour. Sometime they receive visits from Theophany, a sister of the parish of Saint Joseph, in Larnaca. She brings them clothes and she prays with the Christian ones. Less often they receive visits by UNHCR officials. For the time remaining, there is absolutely nothing to do in Block 10, from morning to evening. Policemen are curious about my visit. In fact C. has been refusing to see his wife and children for two weeks. He explained to me he is protesting against his detention. He has been detained in Block 10 for seven months. He’s Nigerian, and has been living in Cyprus since 2001. His request for asylum was rejected last 16th May. And now he has no money to pay a lawyer for an appeal. But this is not the only problem. The point is that C. is married to a Filipino woman who lives here in Nicosia. And they have two sons, 5 and 3 years old. The older one, two weeks ago, asked him why ... Why is he in prison? Is he a bad man? Doesn’t he love him and his mom enough? C. has not yet been able to find a good answer.

Policemen are curious about my visit. In fact C. has been refusing to see his wife and children for two weeks. He explained to me he is protesting against his detention. He has been detained in Block 10 for seven months. He’s Nigerian, and has been living in Cyprus since 2001. His request for asylum was rejected last 16th May. And now he has no money to pay a lawyer for an appeal. But this is not the only problem. The point is that C. is married to a Filipino woman who lives here in Nicosia. And they have two sons, 5 and 3 years old. The older one, two weeks ago, asked him why ... Why is he in prison? Is he a bad man? Doesn’t he love him and his mom enough? C. has not yet been able to find a good answer. Cyprus is 70 km far from Turkey and 100 km from Syria. Two-thirds of the island are under the government of the Republic of Cyprus, which since May 2004 is part of the European Union. The remaining territory in the north is occupied by the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, proclaimed after the Turkish military intervention in 1974. Around 800,000 Cypriots and 170,000 immigrants live on the island. About 30,000 are EU citizens; 60,000 are non-EU (Filipinos, Pakistanis, Sri Lankans), mostly employed in domestic works and catering; 20,000 are Greeks from the Caucasus and about 50,000 are undocumented migrants, mainly Syrians and Turks. Asylum seekers are about 11,000. The majority of them comes from Syria, Sri Lanka, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Iraq, Palestine, Iran, and Georgia. A quite small figure, but sufficient to make Cyprus the first EU country for the impact of the number of asylum seekers on the number of inhabitants. Until now, recognized refugees are about 500, and 95% of them are Iraqis and Palestinians. In 2007 the rate of asylum recognition was 1.25%. One of the lowest in Europe. And the repatriations are around 2,500 per year. Cristina Palmas, an official of the UNHCR, gave me all these figures. I met her in the headquarter of UNFICYP, the UN mission in Cyprus.

Cyprus is 70 km far from Turkey and 100 km from Syria. Two-thirds of the island are under the government of the Republic of Cyprus, which since May 2004 is part of the European Union. The remaining territory in the north is occupied by the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, proclaimed after the Turkish military intervention in 1974. Around 800,000 Cypriots and 170,000 immigrants live on the island. About 30,000 are EU citizens; 60,000 are non-EU (Filipinos, Pakistanis, Sri Lankans), mostly employed in domestic works and catering; 20,000 are Greeks from the Caucasus and about 50,000 are undocumented migrants, mainly Syrians and Turks. Asylum seekers are about 11,000. The majority of them comes from Syria, Sri Lanka, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Iraq, Palestine, Iran, and Georgia. A quite small figure, but sufficient to make Cyprus the first EU country for the impact of the number of asylum seekers on the number of inhabitants. Until now, recognized refugees are about 500, and 95% of them are Iraqis and Palestinians. In 2007 the rate of asylum recognition was 1.25%. One of the lowest in Europe. And the repatriations are around 2,500 per year. Cristina Palmas, an official of the UNHCR, gave me all these figures. I met her in the headquarter of UNFICYP, the UN mission in Cyprus.The Refugee law was approved in 2000. In 2002 the UNHCR transferred all the files to the Ministry of Interior. The law is good – says Palmas - but it is not applied. Every asylum seeker should receive 500 euro per month from the State, but only 300 people were supported in 2007. The other ten thousand asylum seekers have to survive somehow during a period of time of two to four years. But the law doesn’t allow them to work. The only job they can ask for is in the agriculture. But the farms are in crisis and they don’t require any more workforce. Therefore the national contract provides a salary of 300 euro per month, in a country where one coffee costs 3 euro. Palmas also shows me how, with around 11,000 applications for asylum, the government has provided only one guesthouse with just 43 places, reserved to women, children and families.

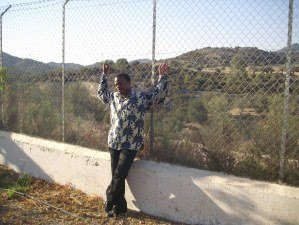

The center is located four kilometers from Kophinou, about 90 kilometers south of Nicosia. Opened in 1997 for gypsies, in 2003 it was dedicated to the asylum seekers. Two rows of containers are placed over a cement area, in the middle of the mountains, with a fence all around. Inside each container there are three double rooms. But the structures are half-empty. Many people have left. The centre is very isolated, and they preferred the precariousness of the capital. Rachel instead remained in the camp. She is from Cameroon. Since 2006 she is waiting the answer to her application for asylum. She spends all the day chatting in the internet point. There is nothing else to do here. The State pays her 80 euro per month. She is forbidden to work, except in the countryside. I went to Kophinou accompanied by Jonathan, a Congolese refugee. Before leaving, he asks me to take a picture of him against the fence. We are in a cage, he jokes. After four years of limbo, he has still some irony.

The center is located four kilometers from Kophinou, about 90 kilometers south of Nicosia. Opened in 1997 for gypsies, in 2003 it was dedicated to the asylum seekers. Two rows of containers are placed over a cement area, in the middle of the mountains, with a fence all around. Inside each container there are three double rooms. But the structures are half-empty. Many people have left. The centre is very isolated, and they preferred the precariousness of the capital. Rachel instead remained in the camp. She is from Cameroon. Since 2006 she is waiting the answer to her application for asylum. She spends all the day chatting in the internet point. There is nothing else to do here. The State pays her 80 euro per month. She is forbidden to work, except in the countryside. I went to Kophinou accompanied by Jonathan, a Congolese refugee. Before leaving, he asks me to take a picture of him against the fence. We are in a cage, he jokes. After four years of limbo, he has still some irony. Jonathan is one of the ghosts of a whole generation disappeared from Kivu, in the so called Democratic Republic of Congo. People who have not been killed, have all escaped, he says. He fled with the whole family. He used to work in a local NGO and worked as a journalist. His descent into hell began on 30th October 1996, in his hometown of Goma. The Banyamulenge army bombed the refugee camps of Uvira-Bukavu-Goma. Thousands of people died. And the first war of Congo started, opposing the rebels to the former Zaire army. Jonathan escaped. First in Uganda, then in Kenya. In 2004, he managed to fly from Nairobi to Damascus, in Syria. From there, he crossed illegally the Turkish border in Hatay and reached Istanbul. He had initially thought of Greece. But then he convinced himself that Cyprus could also be a right choice, since the country had just entered the EU. He bought a fake passport and flew to Erçan, the airport in the north of the island occupied by Turkey. A few days later, he was caught by the Cypriot police while crossing the border of the green line in Nicosia with four other people. Jonathan was injured to a leg, after he jumped from the wall which separates the Turkish side of the city from the Greek one. One of the policemen repeatedly beat him on the leg. Then they were returned back. Jonathan was unable to walk. But anyway he managed to cross the barbed wire fence, few hours later, dragging the wounded leg. By chance, another Congolese met him on the road and host him at his home, until his leg healed.

Jonathan is one of the ghosts of a whole generation disappeared from Kivu, in the so called Democratic Republic of Congo. People who have not been killed, have all escaped, he says. He fled with the whole family. He used to work in a local NGO and worked as a journalist. His descent into hell began on 30th October 1996, in his hometown of Goma. The Banyamulenge army bombed the refugee camps of Uvira-Bukavu-Goma. Thousands of people died. And the first war of Congo started, opposing the rebels to the former Zaire army. Jonathan escaped. First in Uganda, then in Kenya. In 2004, he managed to fly from Nairobi to Damascus, in Syria. From there, he crossed illegally the Turkish border in Hatay and reached Istanbul. He had initially thought of Greece. But then he convinced himself that Cyprus could also be a right choice, since the country had just entered the EU. He bought a fake passport and flew to Erçan, the airport in the north of the island occupied by Turkey. A few days later, he was caught by the Cypriot police while crossing the border of the green line in Nicosia with four other people. Jonathan was injured to a leg, after he jumped from the wall which separates the Turkish side of the city from the Greek one. One of the policemen repeatedly beat him on the leg. Then they were returned back. Jonathan was unable to walk. But anyway he managed to cross the barbed wire fence, few hours later, dragging the wounded leg. By chance, another Congolese met him on the road and host him at his home, until his leg healed. Four years after this incident, Jonathan is still waiting for an answer to his application for asylum. He survives thanks to the welfare program. In the meanwhile he managed to provide a student visa to his wife. They are now expecting a baby. A child will help them to leave this limbo time behind them and to look towards the future. They will not end up like Joao, another Congolese, who every day comes to the Kisa internet point asking in an obsessive way if anyone has found the documents he lost… Unfortunately he also lost his mind, after too many months in Block Ten. I hear him speak as I’m writing the last sentences of this article, in the same internet point. In front of me, behind the screen, Durjan is smiling. He finally sent some picture of himself by email in Nepal. He arrived in Cyprus in 2003. His son is now nine years old, and he is still living in Nepal, with his mother. Now he won't be able to forget his father's face, as it may have easily happened after five years of distance.

Four years after this incident, Jonathan is still waiting for an answer to his application for asylum. He survives thanks to the welfare program. In the meanwhile he managed to provide a student visa to his wife. They are now expecting a baby. A child will help them to leave this limbo time behind them and to look towards the future. They will not end up like Joao, another Congolese, who every day comes to the Kisa internet point asking in an obsessive way if anyone has found the documents he lost… Unfortunately he also lost his mind, after too many months in Block Ten. I hear him speak as I’m writing the last sentences of this article, in the same internet point. In front of me, behind the screen, Durjan is smiling. He finally sent some picture of himself by email in Nepal. He arrived in Cyprus in 2003. His son is now nine years old, and he is still living in Nepal, with his mother. Now he won't be able to forget his father's face, as it may have easily happened after five years of distance.For more information:

Parlement Européen: Rapport de visite à Chypre